Lex Walton is Not Famous, and it’s All My Fault

An interview-aided dive into the satirical, self-contradictory brand indie rock ’n’ roller Alex Walton never meant to build

01 · 12 · 2025

The first time I saw Alex Walton’s work, it felt like a digital hallucination. A blonde woman, mascara streaking down her face, was singing her lungs out on Omegle while a rotation of dudes flashed her like some deranged sideshow. This music video drifted onto my feed almost exactly two years ago, uninvited and unforgettable. Within minutes, I was combing through her Spotify page, wondering who the hell would make something like that—and why it worked so well.

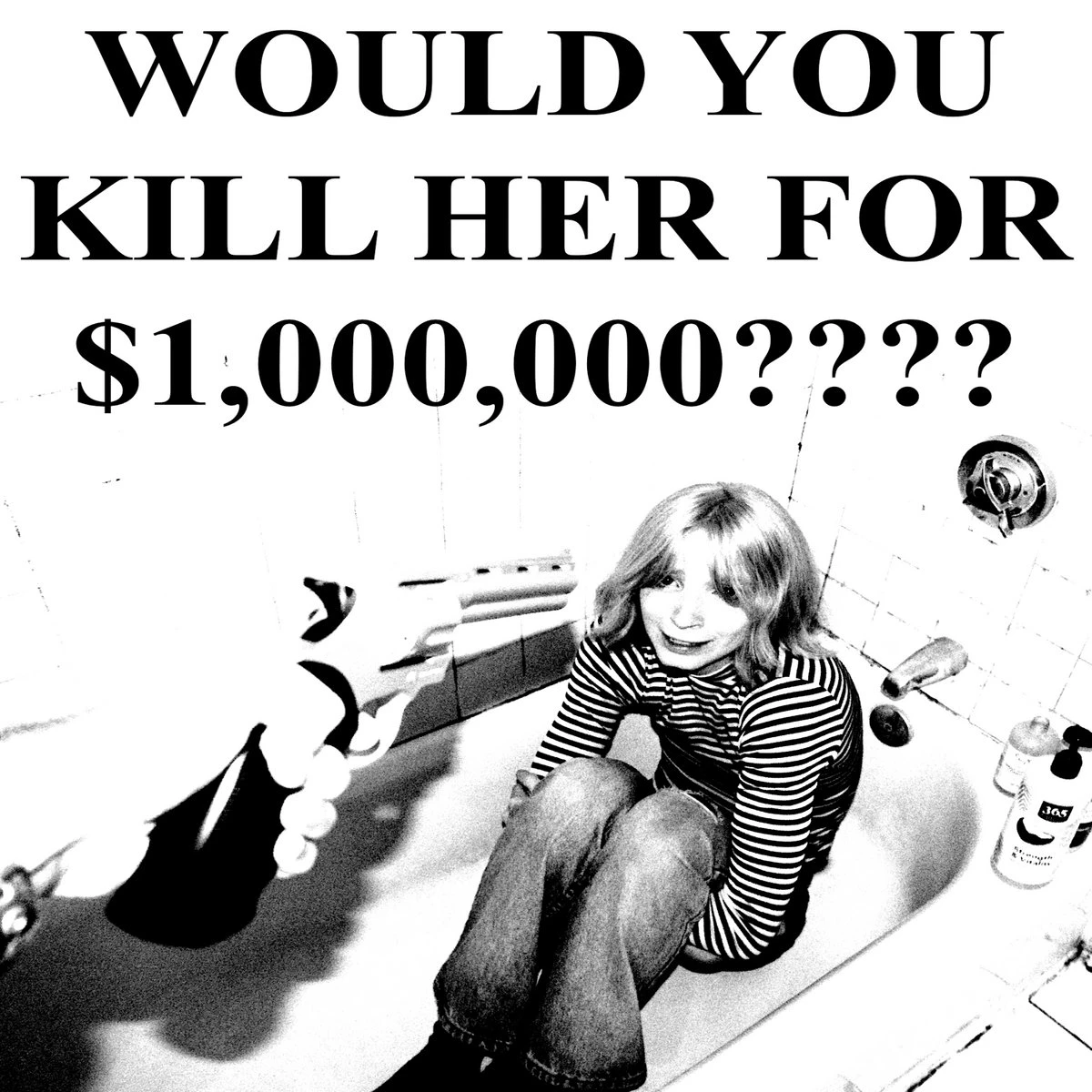

Cover artwork for WOULD YOU KILL HER FOR $1,000,000???? by Alex Walton

Waiting for me at the gates of a fairly sizeable discography were guns, provocative copy, and a clear intent to shock. The unhinged theatrics I had witnessed a short while ago were evidently not a one-off. I proceeded to make my way down the page, eventually landing on the artist bio:

neurotic troubadour of the heart, rock and roll soul survivor, author of “the sound rocker’s prayer”, lex walton is not famous, and it’s all your fault. look at her, you made her cry. she does it all for you.

It read like a manifesto disguised as a joke.

Another eccentric indie specimen to add to my ever-growing Pokédex of artists who feel like they crawled straight out of the internet’s collective subconscious. Perfect.

Lex has since become one of my favourite artists. Beyond the songs themselves, what’s kept me hooked is the identity she’s carved out for herself—this deliberately hyper-confessional, almost disarmingly sincere persona that feels equal parts performance and compulsion. And I thought it’d be worthwhile to try and pick that apart a little.

She was even kind enough to indulge me in a brief text interview. Absolute legend.

Another eccentric indie specimen to add to my ever-growing Pokédex of artists who feel like they crawled straight out of the internet’s collective subconscious. Perfect.

Lex has since become one of my favourite artists. Beyond the songs themselves, what’s kept me hooked is the identity she’s carved out for herself—this deliberately hyper-confessional, almost disarmingly sincere persona that feels equal parts performance and compulsion. And I thought it’d be worthwhile to try and pick that apart a little.

She was even kind enough to indulge me in a brief text interview. Absolute legend.

The Lex Walton Orchestra, photographed by Young Ye

To me, Lex embodies the archetype of the contemporary DIY musician: terminally online, twenty-something, oscillating between day jobs while churning out art with the urgency of someone who doesn’t really have a choice in the matter. Her music in the last few years has been heavily centered around sharing deeply personal thoughts and anecdotes, claiming she’s “completely lost any ability for metaphor, storytelling, or anything other than relaying events in [her] life”.

This candidness, however, is not limited to just her music. Her online presence is best described in the most literal sense: she is a true blue “poster”—a creature of the feed who treats the timeline like a running commentary on her life.

This candidness, however, is not limited to just her music. Her online presence is best described in the most literal sense: she is a true blue “poster”—a creature of the feed who treats the timeline like a running commentary on her life.

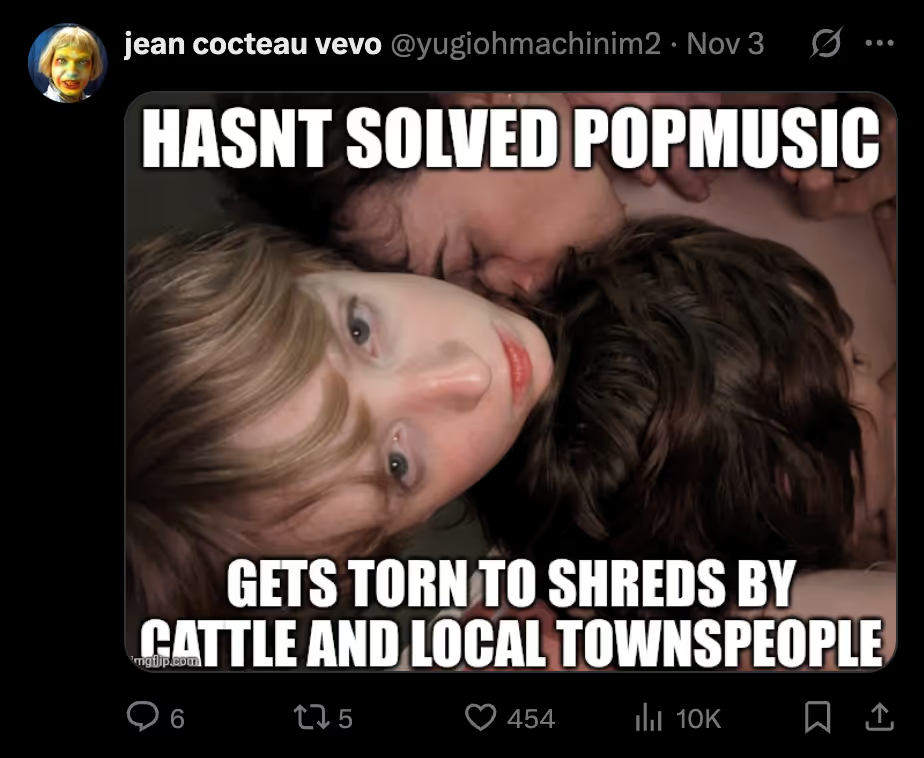

Miscellaneous snippets from Lex’s Twitter handle

Copious amounts of shitposts aside, Lex does not shy away from sharing her day-to-day life and thoughts at a level most artists wouldn’t dare. I’ve been on Instagram Lives where she just lets random viewers hop on video and chats shit with them the way you would with a stranger at a bar. And through these snippets, we’re made privy to the happenings of her life, big and small, whether it’s the exact burger she inhaled five minutes ago or the new part-time job she picked up that week.

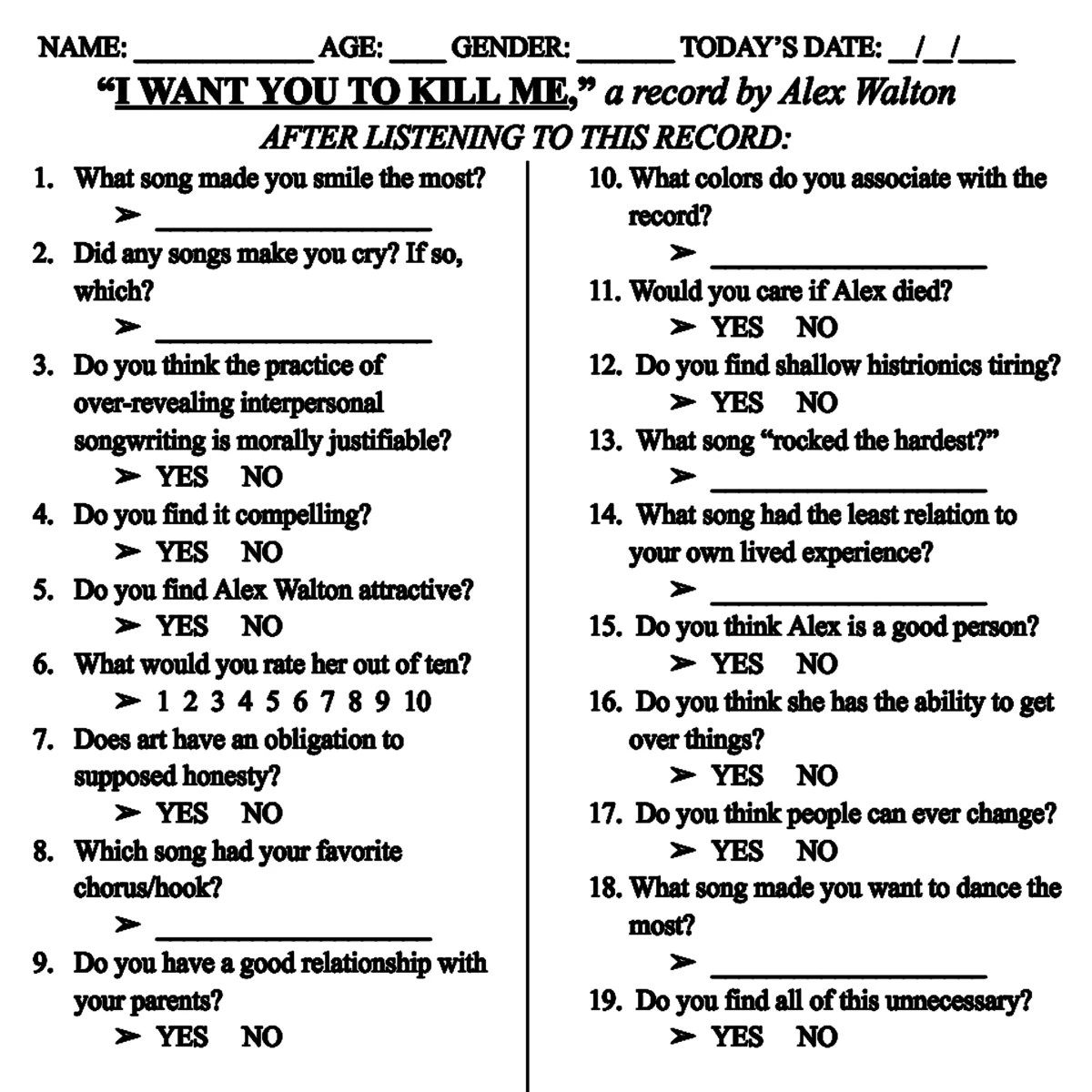

The cover art for her album I WANT YOU TO KILL ME (designed to look like a psych ward intake form photocopied five times over) provokes listeners to engage with her more intimately than they might have ever expected. Safe to say, I’ve never had another artist ask me what I’d rate them out of 10, or whether I’d care if they died.

The cover art for her album I WANT YOU TO KILL ME (designed to look like a psych ward intake form photocopied five times over) provokes listeners to engage with her more intimately than they might have ever expected. Safe to say, I’ve never had another artist ask me what I’d rate them out of 10, or whether I’d care if they died.

Cover artwork for I WANT YOU TO KILL ME by Alex Walton, which just had its 2-year anniversary. Happy birthday.

Lex seems to actively foster a significant level of intimacy and vulnerability with her audience. “The progression of my artistic practice has culminated in almost a complete dissolution of [the divide between Alex Walton, the artist, and Lex Walton, the person]”, she reflected in an interview leading up to the release of I WANT YOU TO KILL ME.

One thing I was particularly curious about pertaining to this presentation was the degree of parasociality that fans developed with Lex and how that affected their engagement with her. “Well, when I make this work that tells you so much about myself, it invites this behaviour in people to treat you a certain way. I’d say that these decisions [regarding my presentation] are less so inviting this kind of parasociality (although they absolutely are to a certain extent) and more satirising this relationship and other artists that clamour for validation from their audiences”, she clarified to me.

“I really don’t like when a power dynamic arises from another person ‘knowing’ me while I don’t know them, and they sum me up to what they imagine to be me and treat me as such. I want to be a human being, not a handle to yell out! But maybe that’s just ungrateful of me to say. I am at the level where I really do relish every time someone stops me on the street and tells me what my work means to them; these are invaluable experiences and help me keep going.”

As both a brand designer and a fan, this exaggerated sense of vulnerability was what I identified most in her brand, and I was unsure how much of it was carefully curated to serve the persona of ‘Alex Walton’.

“I’m not sure if there is a conscious creation of a ‘character’ at all, but of course [that’s] unavoidable. The photographer chooses what is not in the frame as much as she chooses what is in it”, Lex remarked.

So it genuinely threw me when she expressed nothing short of disdain for conventional brand development, given how strong hers felt to me. “I am a narcissist and crave attention, but I am also both incapable of and disgusted by the usual avenues of ‘engagement’ and ‘brand building.’ As such, I just post a lot. I love images and sharing images and seeing images and sharing what I love with others”, she said.

Nevertheless, as satirical as many of these practices may be, they also undoubtedly make Lex feel more “within reach“. And as much as she eschews the idea of brand building, I still hold firm on the stance that she’s built a damn good one for herself.

One thing I was particularly curious about pertaining to this presentation was the degree of parasociality that fans developed with Lex and how that affected their engagement with her. “Well, when I make this work that tells you so much about myself, it invites this behaviour in people to treat you a certain way. I’d say that these decisions [regarding my presentation] are less so inviting this kind of parasociality (although they absolutely are to a certain extent) and more satirising this relationship and other artists that clamour for validation from their audiences”, she clarified to me.

“I really don’t like when a power dynamic arises from another person ‘knowing’ me while I don’t know them, and they sum me up to what they imagine to be me and treat me as such. I want to be a human being, not a handle to yell out! But maybe that’s just ungrateful of me to say. I am at the level where I really do relish every time someone stops me on the street and tells me what my work means to them; these are invaluable experiences and help me keep going.”

As both a brand designer and a fan, this exaggerated sense of vulnerability was what I identified most in her brand, and I was unsure how much of it was carefully curated to serve the persona of ‘Alex Walton’.

“I’m not sure if there is a conscious creation of a ‘character’ at all, but of course [that’s] unavoidable. The photographer chooses what is not in the frame as much as she chooses what is in it”, Lex remarked.

So it genuinely threw me when she expressed nothing short of disdain for conventional brand development, given how strong hers felt to me. “I am a narcissist and crave attention, but I am also both incapable of and disgusted by the usual avenues of ‘engagement’ and ‘brand building.’ As such, I just post a lot. I love images and sharing images and seeing images and sharing what I love with others”, she said.

Nevertheless, as satirical as many of these practices may be, they also undoubtedly make Lex feel more “within reach“. And as much as she eschews the idea of brand building, I still hold firm on the stance that she’s built a damn good one for herself.

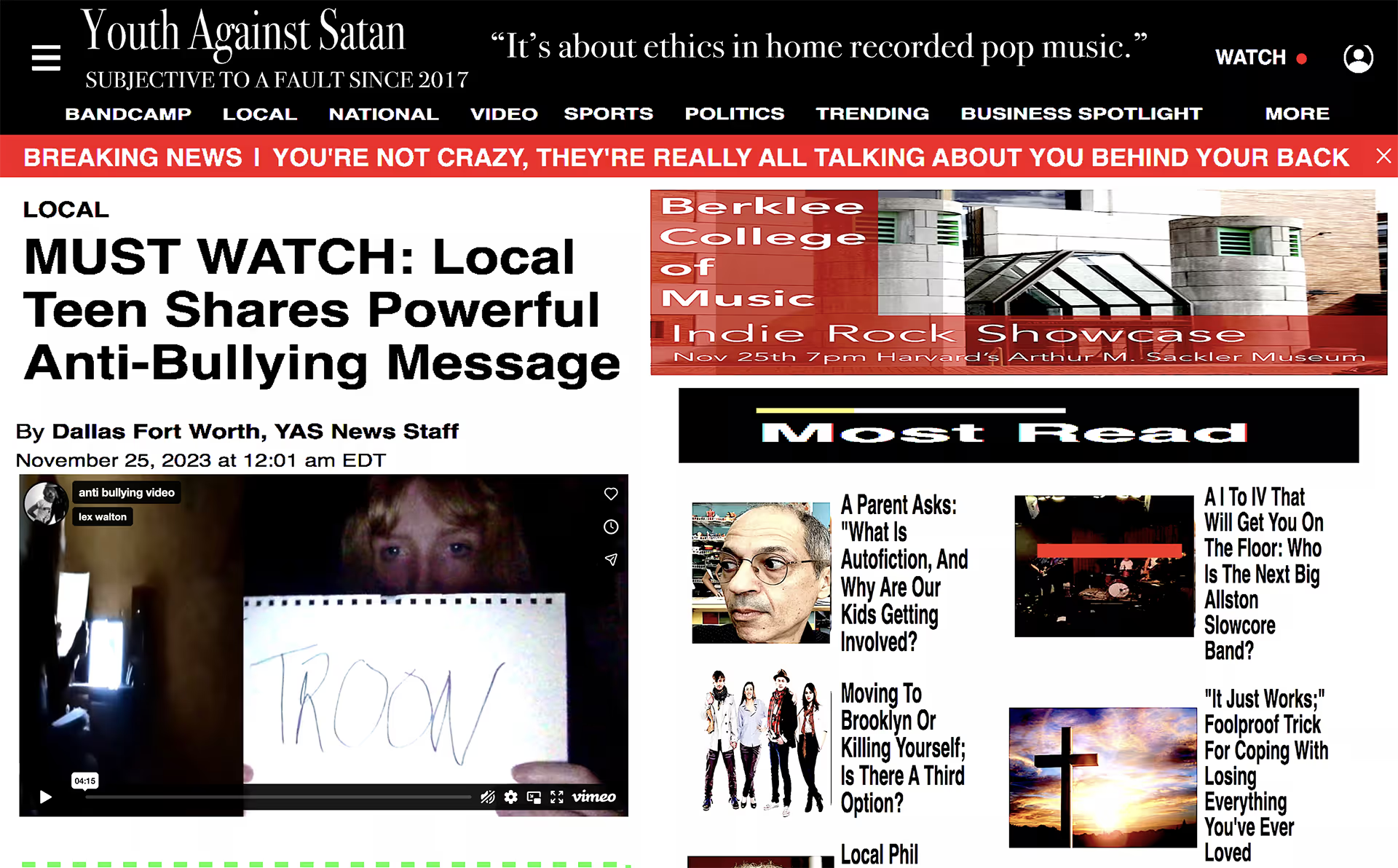

Website landing page for Lex’s self-started label, Youth Against Satan

One of the first facets of Alex Walton that you notice is her visual identity: abrasive and defiantly lo-fi.

Her self-started label, Youth Against Satan’s web landing page revels in the anxiety-inducing clutter of a bootleg anime streaming site from 2010, daring you to figure out what you can even click—joke’s on you, the entire site is a single image.

Her music videos are no different. Many of them look like they’ve been deep-fried and run through a blender ten times over.

Her self-started label, Youth Against Satan’s web landing page revels in the anxiety-inducing clutter of a bootleg anime streaming site from 2010, daring you to figure out what you can even click—joke’s on you, the entire site is a single image.

Her music videos are no different. Many of them look like they’ve been deep-fried and run through a blender ten times over.

Stills from the music videos for the tracks lonesome town and GIRLFRIEND SONG

When asked about the curation of this visual language and what emotions she hoped to evoke in the viewer, Lex told me about her fascination with “rot” and “pushing images to their limits”.

“Reprocessing is something very important to me. Filming, then filming the screen it is playing back on, and filming the screen doing that while it films, skewing perspectives, printing out, crumpling, rescanning, doing [that] again and again. Making everything feel like a third-generation copy; not ‘vintage’ or ‘nostalgic’, but worn down and shitty and cheap.”

She feels a need to “contort” and “hyper-saturate”, something that perhaps is an apt representation of her artist persona. Like a hyper-saturating image losing data from being screenshotted a hundred times over, leaving behind only the most defining features of the original, Alex Walton spotlights the most defining traits of artists in the internet age, further stylised and exaggerated.

This form of deep-fried imagery and “anti-design” has been in the zeitgeist for a good bit now, but it can be deceptively hard to pull off well. There’s a gulf between the chaotic charm of a genuine shitpost—born out of the limits of bargain-bin software—and a trained designer trying to mimic that aesthetic with an arsenal of overpriced tools at their disposal. Lex’s videos are exquisitely composed, yet feel like they were made under the tight constraints of an indie artist’s limited time and resources. I’ll admit, I always wondered if she just happened to work with a graphic designer who had mastered the art of toeing that line, but it turns out that what I was seeing was simply the reality of how the videos are produced.

With a strong desire to retain authorship, Lex said she makes everything herself without very much external aid to speak of. And when asked about her perceived sense of expertise in the craft, she told me that she doesn’t consider herself a professional designer so much as “an amateur, in the Maya Deren sense”, someone who uses whatever’s within arm’s reach with obsessive intentionality.

“Everything is made on what is available in front of me, namely the OSX Preview app and iMovie, and I try to push these programs that are very lacking to their limits.”

“Reprocessing is something very important to me. Filming, then filming the screen it is playing back on, and filming the screen doing that while it films, skewing perspectives, printing out, crumpling, rescanning, doing [that] again and again. Making everything feel like a third-generation copy; not ‘vintage’ or ‘nostalgic’, but worn down and shitty and cheap.”

She feels a need to “contort” and “hyper-saturate”, something that perhaps is an apt representation of her artist persona. Like a hyper-saturating image losing data from being screenshotted a hundred times over, leaving behind only the most defining features of the original, Alex Walton spotlights the most defining traits of artists in the internet age, further stylised and exaggerated.

This form of deep-fried imagery and “anti-design” has been in the zeitgeist for a good bit now, but it can be deceptively hard to pull off well. There’s a gulf between the chaotic charm of a genuine shitpost—born out of the limits of bargain-bin software—and a trained designer trying to mimic that aesthetic with an arsenal of overpriced tools at their disposal. Lex’s videos are exquisitely composed, yet feel like they were made under the tight constraints of an indie artist’s limited time and resources. I’ll admit, I always wondered if she just happened to work with a graphic designer who had mastered the art of toeing that line, but it turns out that what I was seeing was simply the reality of how the videos are produced.

With a strong desire to retain authorship, Lex said she makes everything herself without very much external aid to speak of. And when asked about her perceived sense of expertise in the craft, she told me that she doesn’t consider herself a professional designer so much as “an amateur, in the Maya Deren sense”, someone who uses whatever’s within arm’s reach with obsessive intentionality.

“Everything is made on what is available in front of me, namely the OSX Preview app and iMovie, and I try to push these programs that are very lacking to their limits.”

From playing videos on broken phone screens to projecting images from a music video she’s making a sequel to, Lex uses just about anything at hand to great effect. Clip from the music video for SHAME MUSIC 2.

And while on the topic of visual character, I’d be remiss to gloss over her live sets (which I’ll probably only ever see via a screen, sigh). You’ll see clips of Lex throwing herself around the stage, allowing her body to express whatever it feels like screaming out.

“I simply try to appear as I am in the singular, the individual, to be projected on as I project outwards, the Mausian ‘hysterical body’, to not be above or below but at level”, she mused when asked about her public presentation.

Referring to John Maus’ erratic and emotionally charged performance style, Lex’s physicality on stage abandons any of the satire or irony that could be found on her digital presence, leaving room only for resounding sincerity. You see here the same jarring, yet transfixing vulnerability that is present in a music video of a woman subjecting herself to the worst of online anonymity. This live physicality kinda completes the picture her visuals start—sincerity pushed past all the irony.

“I simply try to appear as I am in the singular, the individual, to be projected on as I project outwards, the Mausian ‘hysterical body’, to not be above or below but at level”, she mused when asked about her public presentation.

Referring to John Maus’ erratic and emotionally charged performance style, Lex’s physicality on stage abandons any of the satire or irony that could be found on her digital presence, leaving room only for resounding sincerity. You see here the same jarring, yet transfixing vulnerability that is present in a music video of a woman subjecting herself to the worst of online anonymity. This live physicality kinda completes the picture her visuals start—sincerity pushed past all the irony.

Over time, these recurring motifs crystallise into a recognisable code: a brand, whether she claims it or not. This is where her work slips into the classic commodity-aesthetics paradox. As we dive deeper, it’s worthwhile taking the aid of a little theory.

In his seminal critique of commodity-aesthetics, Haug defines the act of purchasing as one set in motion by the promise of “use-value” before any actual use, a use-value that is carried on an aesthetic surface detachable from the actual function of the commodity. And for musicians, that promise is often more than just the music.

In an age where commercially oriented slop gets churned out by the day and audiences mindlessly consume whatever the algorithm shoves at them, the indie art scene ends up functioning as a kind of refuge, a place people turn to when they want to feel like they’re choosing something rather than being fed it. Indie rock, especially, has always operated as both an aesthetic and a status economy. Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital helps explain why: within these circles, authenticity is less a feeling and more a coded kind of knowledge that signals taste, discernment and belonging.

Once you see it through that lens, indie rock starts to look strangely similar to the world of high art. Its value system rewards obscurity, insider knowledge and distance from mass appeal; the harder it is to access socially or culturally, the more “authentic” it becomes. That authenticity becomes a currency through which fans, scenes and artists can position themselves.

As an active participant of the thriving New York underground scene, Lex often finds herself closely entangled with some of the very best making art today. And of course, since she brings us along for the ride, we the audience seemingly get ground-level access to moments that you’d usually only see in a documentary made after an artist’s heyday. It’s not everyday that you get to see practice sessions for the opening act of an Ezra Furman show, after all. And it might be that I find even more value in this because, sitting halfway across the world, I feel physically detached from the spaces a lot of my favourite artists come up in. Regardless, indie rock satisfies a desire among audiences for social differentiation, and my proximity to it via Lex gives me the cultural credit I so crave.

More so today than ever before, music audiences, especially those consciously tuning into the indie scene, are acutely aware of where an artist’s primary revenue stream comes from. They know that the industry is built to shaft the artist and that fans must support them if they want the work to continue. Whether that’s by attending shows, buying merch or vinyl, or directly putting money into their pockets through platforms like Bandcamp and Patreon, the stronger one’s emotional connection with an artist, the more likely one is to offer financial support.

Therein lies the contradiction. The anti-branding and intimacy meant to critique commodification still act as promotional surfaces that realise exchange-value—a tension at the centre of Lex’s entire ecosystem.

In his seminal critique of commodity-aesthetics, Haug defines the act of purchasing as one set in motion by the promise of “use-value” before any actual use, a use-value that is carried on an aesthetic surface detachable from the actual function of the commodity. And for musicians, that promise is often more than just the music.

In an age where commercially oriented slop gets churned out by the day and audiences mindlessly consume whatever the algorithm shoves at them, the indie art scene ends up functioning as a kind of refuge, a place people turn to when they want to feel like they’re choosing something rather than being fed it. Indie rock, especially, has always operated as both an aesthetic and a status economy. Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital helps explain why: within these circles, authenticity is less a feeling and more a coded kind of knowledge that signals taste, discernment and belonging.

Once you see it through that lens, indie rock starts to look strangely similar to the world of high art. Its value system rewards obscurity, insider knowledge and distance from mass appeal; the harder it is to access socially or culturally, the more “authentic” it becomes. That authenticity becomes a currency through which fans, scenes and artists can position themselves.

As an active participant of the thriving New York underground scene, Lex often finds herself closely entangled with some of the very best making art today. And of course, since she brings us along for the ride, we the audience seemingly get ground-level access to moments that you’d usually only see in a documentary made after an artist’s heyday. It’s not everyday that you get to see practice sessions for the opening act of an Ezra Furman show, after all. And it might be that I find even more value in this because, sitting halfway across the world, I feel physically detached from the spaces a lot of my favourite artists come up in. Regardless, indie rock satisfies a desire among audiences for social differentiation, and my proximity to it via Lex gives me the cultural credit I so crave.

More so today than ever before, music audiences, especially those consciously tuning into the indie scene, are acutely aware of where an artist’s primary revenue stream comes from. They know that the industry is built to shaft the artist and that fans must support them if they want the work to continue. Whether that’s by attending shows, buying merch or vinyl, or directly putting money into their pockets through platforms like Bandcamp and Patreon, the stronger one’s emotional connection with an artist, the more likely one is to offer financial support.

Therein lies the contradiction. The anti-branding and intimacy meant to critique commodification still act as promotional surfaces that realise exchange-value—a tension at the centre of Lex’s entire ecosystem.

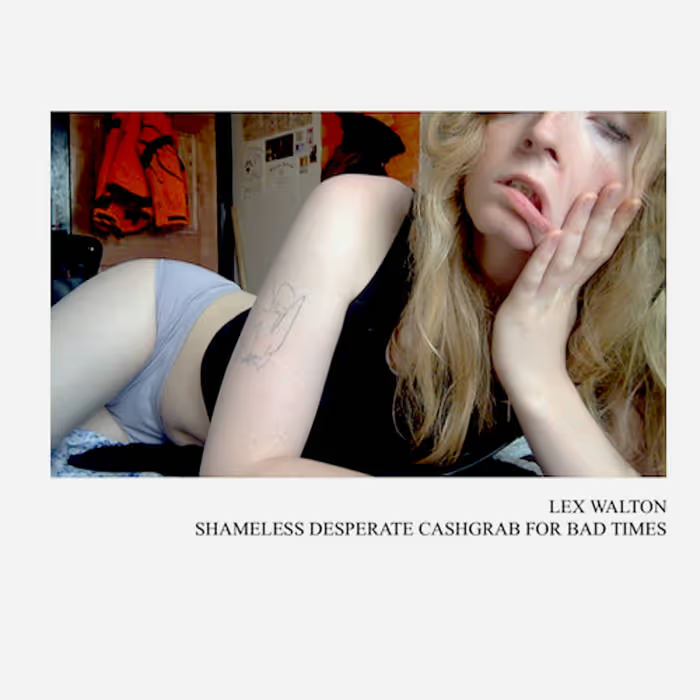

Cover artwork from SHAMELESS DESPERATE CASHGRAB FOR BAD TIMES, a straight-to-Bandcamp release with a project description that reads: “a collection of demos of varying quality from the last year orr so. my health is not good. please buy if you can. theyre good songs i promise”

Where harm enters is in the loop Haug calls the “moulding of sensuality”. When you’re hit with constant images of closeness, it can warp what you think you need, tipping you into this weird cycle of wanting validation or access, sometimes to the point where interactions start to feel a bit predatory. But the same loop can also do the opposite. It can build a kind of steady trust, where intimacy turns into real support instead of invasive demand. The difference isn’t philosophical, it’s practical: it’s about keeping things grounded and real rather than letting everything get swallowed by the logic of access-as-commodity.

And the thing is, the platforms Lex’s brand lives on make all of this more or less unavoidable. Social media runs on slicing people into bite-sized surfaces like clips, captions, covers. Even anti-branding gets scooped up, flattened into a recognisable aesthetic, and sent back into the feed as something the system can package and monetise. Something something capitalism, amirite?

At the end of the day, this exercise was as much a reflection on my parasocial dynamic with Lex as it was an investigation of her artistic presentation and intents. Despite having very little in common with her in terms of life experiences, I feel intimately connected to her music. Paraphrasing what Lex has so eloquently laid out before, such is the strange capacity of pop music to “universalise the specifics”, turning one person’s minutiae into another person’s mirror.

But taking a step back from the music, I have to admit that a not insignificant part of that bond comes from taking the bait—from letting myself be pulled in by the deliberate provocations designed to snag people exactly like me. Being aware of the intent behind the shock value doesn’t neuter its potency by a lot. Not when I enjoy letting it get to me. Recognising that susceptibility feels like part of the point.

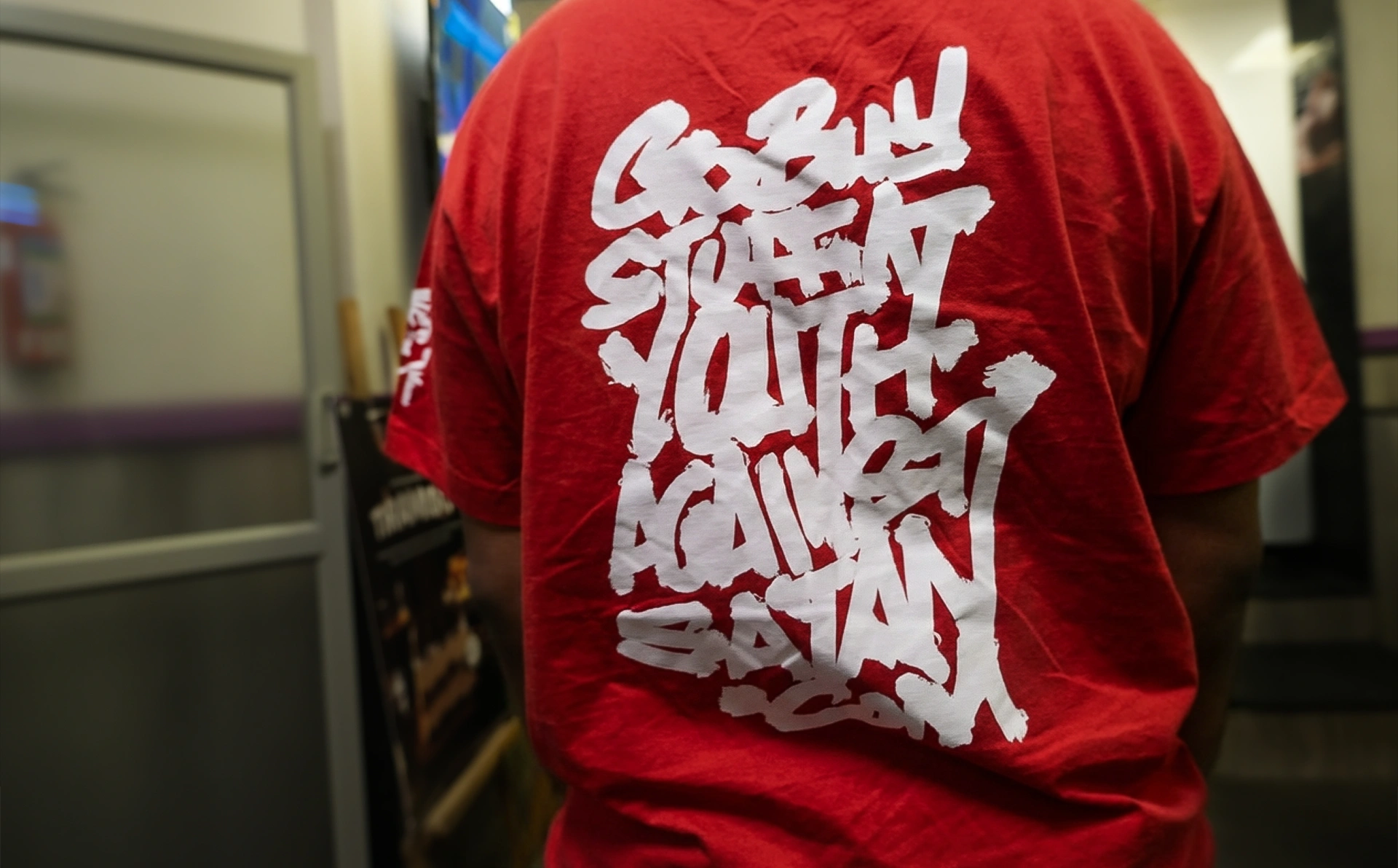

I end where I started as a fan, just with a little more clarity. There’s a tension in how Alex Walton moves through the industry and engages with her fans—ironic, self-aware. A tension that is mirrored within me. One that I somehow decided the best way to express was turning myself into a walking billboard, aware of the irony and choosing it anyway.

And the thing is, the platforms Lex’s brand lives on make all of this more or less unavoidable. Social media runs on slicing people into bite-sized surfaces like clips, captions, covers. Even anti-branding gets scooped up, flattened into a recognisable aesthetic, and sent back into the feed as something the system can package and monetise. Something something capitalism, amirite?

At the end of the day, this exercise was as much a reflection on my parasocial dynamic with Lex as it was an investigation of her artistic presentation and intents. Despite having very little in common with her in terms of life experiences, I feel intimately connected to her music. Paraphrasing what Lex has so eloquently laid out before, such is the strange capacity of pop music to “universalise the specifics”, turning one person’s minutiae into another person’s mirror.

But taking a step back from the music, I have to admit that a not insignificant part of that bond comes from taking the bait—from letting myself be pulled in by the deliberate provocations designed to snag people exactly like me. Being aware of the intent behind the shock value doesn’t neuter its potency by a lot. Not when I enjoy letting it get to me. Recognising that susceptibility feels like part of the point.

I end where I started as a fan, just with a little more clarity. There’s a tension in how Alex Walton moves through the industry and engages with her fans—ironic, self-aware. A tension that is mirrored within me. One that I somehow decided the best way to express was turning myself into a walking billboard, aware of the irony and choosing it anyway.

Unofficial merch I made for myself lol. Photographed by Jishnu.